As an Image and Media Technologist, I am constantly exploring innovative perspectives on art and imagery in relation to technology. Tools like LiDAR, AI, and 3D open up new possibilities to push boundaries. It all starts with a strong vision, a dream that must be realized. Innovation is sometimes the only way forward.

I have always seen the concept of God not as an external force, but as something deeply embedded within the individual, a psychological reality that emerges from within. Over time, I discovered how strongly this aligns with Carl Jung’s perspective, as he saw God as an expression of the Self, the inner drive toward wholeness.

With technology in our hands, we are no longer just observers of the world, we have become creators of new realms. The digital and the imagined merge as we build artificial intelligence, virtual landscapes, and entirely new systems of meaning. In many ways, this creative power mirrors the archetypal role of the mythological creator, a role that now extends beyond myth into reality.

Yet, as this transformation unfolds, the process of individuation becomes more crucial than ever. Only through a deep understanding of the psyche, our own myths, fears, and aspirations, can we engage with technology without losing sight of what makes us human.

As we navigate this future, the fusion of different technologies must not overshadow individuality, artistic expression, and human freedom. A constant dialogue with technology is essential, one that reinforces our connection to both the digital and the deeply human.

In 2018, I started working on perceptron classification models, the simplest neural networks, yet a powerful way to grasp what neural networks fundamentally do. Building on this foundation, I delved deeper, regularly reading papers on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and experimenting on my own.

Still, I often felt limited by my lack of mathematical knowledge. I could grasp the concepts to some extent, but much of it remained highly abstract and difficult to internalize. This also made me skeptical of the so-called AI thought leaders flooding the internet, as the true experts are often seasoned computer scientists working behind the scenes, people you rarely hear from.

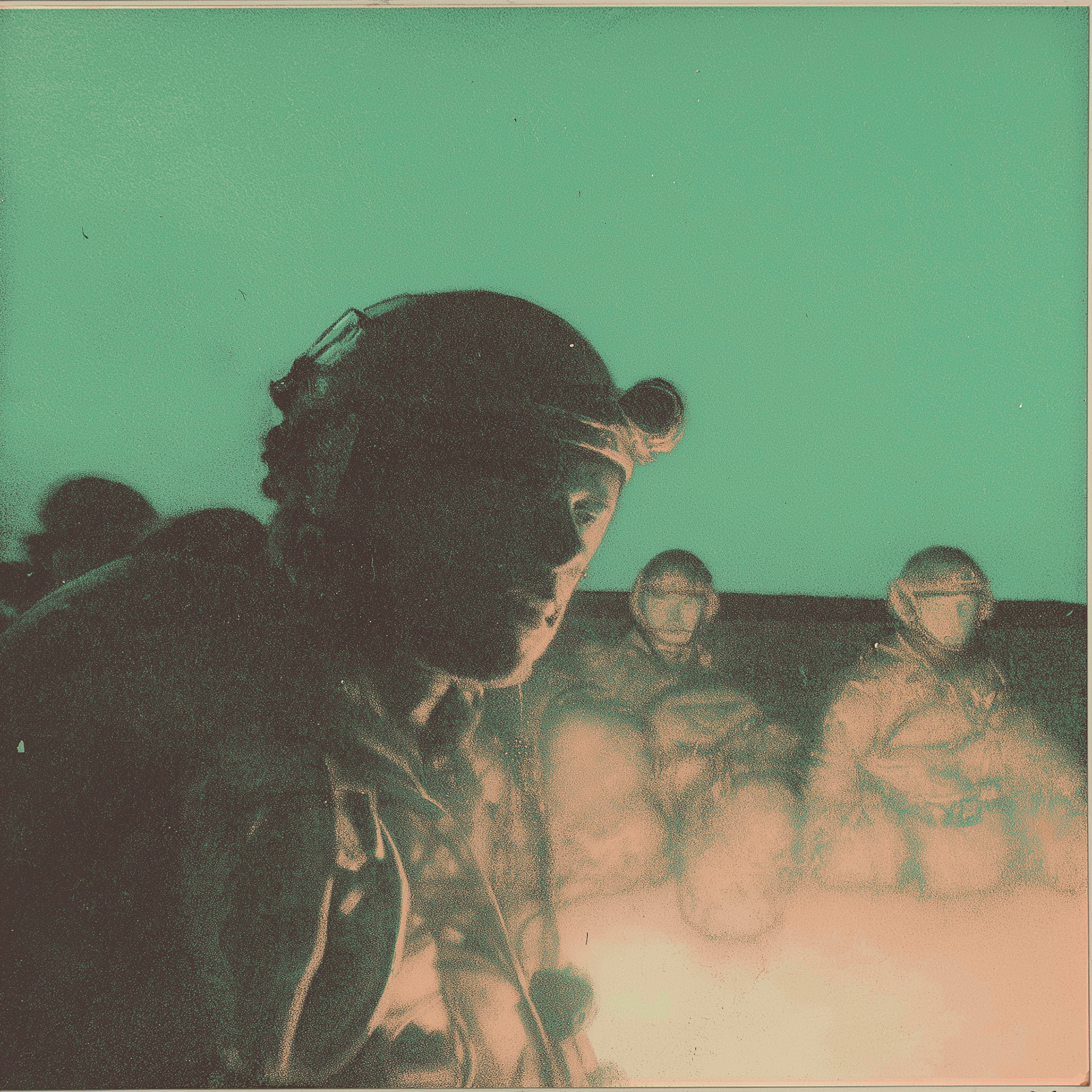

Despite these challenges, experimenting gave me the space to train datasets and observe the outcomes. More often than not, the results were underwhelming. The generated images tended to fall apart, like an abstract painting without structure; they lacked weight, coherence, and depth. It didn’t take long for me to realize that generative imagery and AI art should not be seen as the next evolution of film or photography but as an opposing medium with its own unique visual language and logic.

In the early stages, Google Colab and other tools made experimenting with generative imagery accessible. The results were fragmented, often falling apart, yet their strangeness made them intriguing. Without real reference points, they felt like glimpses into an alternate reality, where structure was both present and absent.

This imbalance reminded me of Mondrian’s obsessive search for harmony. While he meticulously constructed balance, AI-generated imagery often felt weightless, lacking the compositional grounding of traditional visual media. Over time, I saw it not as an extension of photography or film but as an evolutionary offshoot with its own logic.

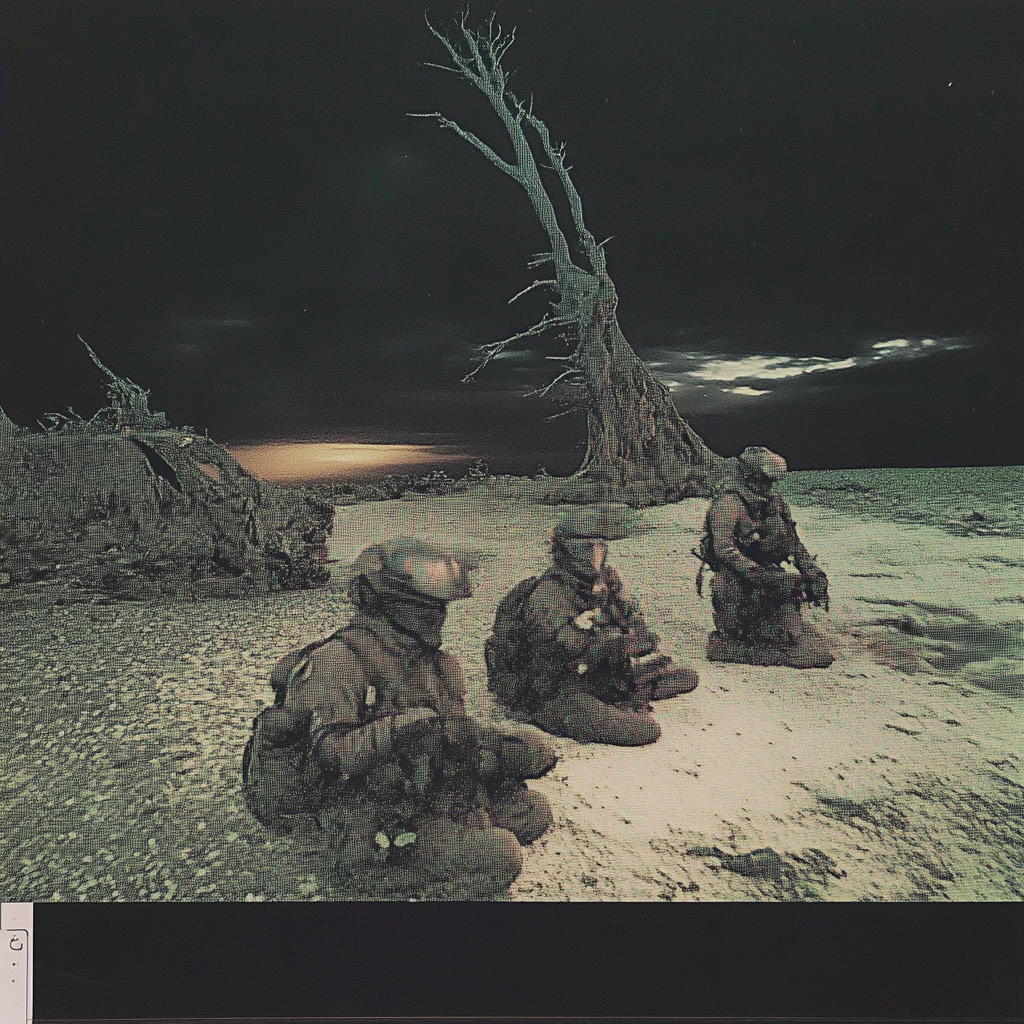

It also brought me back to a book at my grandfather’s house about early humans. The first pages mapped different evolutionary timelines, showing how species branched in unpredictable ways. Generative imagery follows a similar path, trained on real-world visuals yet developing in ways that don’t logically extend from photography or film. Its input is rooted in traditional media, but the way AI reconstructs and mutates it feels more like an emergent genetic process.

Unlike photography, which captures reality, or film, which reconstructs it over time, AI-generated imagery synthesizes data with no clear human intention. Its visual DNA comes from real images, yet its evolution feels alien as if following an unfamiliar timeline.

Alright, there I was. Images could now generate images by compressing them into something new. Exciting… or not. The hype was there, but it faded quickly, at least when it came to GANs. Yet, this was only a fraction of the broader technological shifts reshaping visual creation.

Take Agatha, the recent film Xenia Lodewijks made. During an underwater scene, I had no real control over the focus. AI focus tracking, combined with a magnetic motor in the lens, subtly adjusted the focus in a way that felt almost organic. No artificial sharpness, no harsh transitions, just a seamless, natural pull that captured the perfect shot. This is new, and it’s only the beginning.

I spent hours talking to engineers at the SONY booth at IBC, discussing possible future scenarios. But beyond the technical aspects, I found myself drawn more and more to the philosophical and human foundations of these advancements. I wanted to approach it from a different angle, like making a strategic move in chess. A more analytical, almost metaphysical perspective. So, I started my research again.

Why metaphysics? Perhaps because it allowed me to explore deeper layers within my creative process. Through Bernardo Kastrup’s ideas, I learned that consciousness might not be something produced by physical processes, but rather the fundamental basis from which reality itself emerges. It took me time to understand his theories, and even now I’m still only at the surface.

Eventually, this journey led me to the "hard problem of consciousness," an endpoint in metaphysics that asks how subjective experience arises from physical matter. This unresolved question formed the conceptual core of my short sci-fi film, Moira, which examines precisely the boundary between artificial intelligence and true conscious awareness.

Practically, these ideas influenced my working methods. Using MidJourney, an AI image-generation tool, helped shape the visual style of the film significantly. I also experimented with GAN-generated imagery based on microscopic data we captured in Norway, but the results were mostly unusable, highlighting a clear boundary between machine-generated visuals and genuine human perception. In the end, this philosophical exploration clarified the distinction between intelligence systems and conscious experience, becoming the foundation for Moira.

Apart from all the technical implications and the distortions that generative AI introduces into our images, I kept returning to a more fundamental question: what is consciousness, really? Is consciousness simply having an experience, or is it the ability to recognise, within yourself, that you are experiencing? Opinions on this differ, but it is precisely in that twilight zone between thinking and not thinking, between intentional control and letting go, that the kind of art often arises that we are drawn back to.

Take classical Chinese calligraphy, a language in which writing carries not only meaning, but also movement, rhythm and a way of seeing the world. To create such a character, the maker has to enter a state of concentrated emptiness, a form of consciousness that is both present and absent. The hand moves, but not purely out of will. The character appears, but not out of total control. In Zhang Yimou’s film HERO (2002), the final form of the character is not the result of endless deliberation, but of an embodied cultural consciousness that condenses into a single, concentrated gesture. It is that in-between space that makes human creation so unique?

And it is precisely that in-between space that a generative system will never be able to fully approach. AI can imitate forms, predict structures and replicate styles, but it does not know that exact moment in which a human forgets themselves and, out of that forgetting, arrives at the most recognisable form of expression.